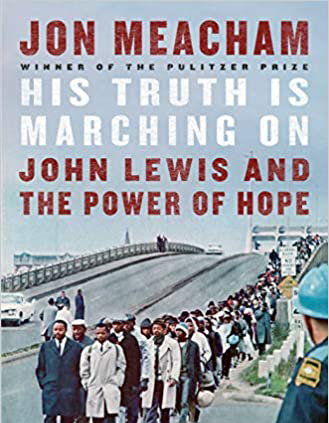

His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope

by Jon Meacham

Booksellers categorize Meacham’s latest work as both history and politics, but it is also about faith, that of both Lewis and Meacham. There is resonance throughout, a recognition of the faith foundation of Lewis’s life and work, a connection to Meacham’s own religious core. What makes this account so rich is that Meacham himself, having been steeped in the gospel, recognizes the same in Lewis. Meacham presents this story as Lewis’s longing for the Beloved Community, “nothing less than the Kingdom of God on earth.”

Lewis grew up with the Scriptures, imagining himself as a preacher who, for lack of a congregation, preached to his family’s chickens. He was “the serious young farm boy presiding over an unruly flock…insistently offering the gospel to an audience disinclined to heed it.” Lewis’s view of the gospel, though, was broader than most. He saw the churches of his youth as focused “mostly on the hereafter and not so much on the here.” Lewis saw the gospel differently, believing that “the Lord had to be concerned with the way we lived our lives right here.” Meacham notes that at the center of Lewis’s life was “the willingness to suffer and die for others – again and again.”

Martin Luther King Jr. introduced him to nonviolent religiously inspired protest but warned him of likely consequences. “Don’t despair if you are condemned…for righteousness sake. Whenever you take a stand for truth and justice you are liable to scorn…to be called a dangerous radical…it might mean going to jail.” King’s words resonated for Lewis, “as though a light turned on in my heart.”

Lewis did go to jail many times and suffered beatings at the hands of both troopers and ordinary citizens who could not abide black people enjoying the same privileges as they. Meacham recounts stories where Lewis puts his life at risk. Integrating a Nashville restaurant, Lewis and another student bought lunch and sat down to eat. At only 2:30 in the afternoon, they were told to leave, that the place was closed. The staff began pouring water on them and turned up the air conditioning, trying to freeze them out. Then the manager told them to leave; he had decided to fumigate the place. He locked the doors and turned on the insecticide. With no escape. Lewis and his friend began sharing Daniel’s story of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the fiery furnace. They, too, thought they would die, poisoned by the insecticide. And they might have, had it not been for an angel in the form of the city fire department. Passersby had seen the cloud of billowing insecticide and mistaken it for smoke. Upon release, Lewis said, “We could have died…I was not eager to die but I was at peace with the prospect of death.” He was 21 years old.

Meacham tells one story of the origin of the Selma marches. Jimmie Lee Jackson, veteran and deacon in the Baptist church, was shot during a protest. During the funeral procession someone proposed carrying young Jimmie back to Montgomery and symbolically laying his casket on the capitol steps. They did not carry the casket to Montgomery, but they did plan a march. On Sunday, March 7, 1965, marchers gathered at the Brown Chapel AME Church. They marched to the Pettus Bridge. When they crested the bridge, they saw a sea of uniforms. They could not go forward and would not turn around. They decided to kneel and pray, but before they got to their knees the officer gave the command “Troopers, advance.”

There were clubs and bullwhips and horses trampling marchers. Lewis was the first to be hit, his skull fractured. “At that moment, I saw death and thought ‘It’s alright – I am doing what I am supposed to do.’” Lewis regained consciousness and was taken to the aptly named Good Samaritan Hospital.

The marchers were not giving up. A call was sent out for clergy of all faiths to come for Sunday, March 21, 1965. It was to this call that our own John Galbreath responded.

Meacham says, “It is difficult to overstate Selma’s significance…not because of a conventional clash of forces but because the conventions of history were turned upside down. Selma changed hearts and minds when Americans watched the brutal forces of the visible world meet the forces of an invisible one, and the clubs and horses and tear gas were, in the end, no match for love and grace and nonviolence. Meacham observes that to Lewis, history “will end not in despair and dust but in hope and harmony with the coming of the Beloved Community. To him, then, politics was not an end but a means to bring about a world in which, in the words of the prophet Micah, every man shall dwell under his own vine and fig tree, and no one shall make him afraid.” Lewis was working for the here and now to be transformed by the infusion of the spirit of Jesus.

NOTE: This summer we saw people throughout the country again standing against racism – people of all colors and ethnicities and gender identities, all ages and religious traditions, a broader coalition than in the 1960s. Overall, there may have been more fist-waving and less knee-bending, but still there were many pockets where the church was prayerfully calling for an end to racism.

– Bobbie Hartman